Honey, I Shrunk the Market!

Why Fewer Public Companies Could Reshape the Future of Investing

Source: Disney/Kobal/Shutterstock

Once upon a time—not so long ago—investors could browse a stock market filled with thousands of choices, from scrappy upstarts to dominant blue chips. But fast-forward to today, and the market looks a lot leaner. In fact, the number of publicly traded companies in the U.S. has shrunk by nearly half over the past two decades.

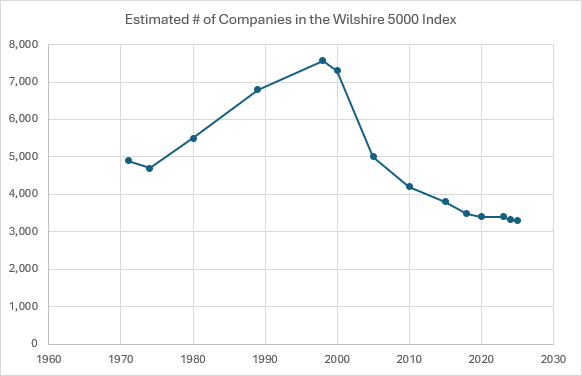

A striking example of this contraction is the Wilshire 5000 Index, once considered the most comprehensive gauge of the U.S. equity market. Despite its name, the index no longer includes 5,000 companies. As of 2024, it tracks just over 3,500 constituents. Originally designed to represent “the entire investable market,” its shrinking roster highlights a broader trend: there simply aren’t enough public companies to fill it anymore.

Source: Wilshire

This shrinking universe of public stocks is more than a statistical curiosity—it’s reshaping the entire investment landscape. With fewer companies going public and more money concentrating into a small number of mega-cap giants, the market has become increasingly top-heavy. For many investors, this has created both blind spots and growing risks.

Why Are There Fewer Public Companies?

The decline isn’t a fluke—it’s a trend with deep structural roots:

The Private Equity and Private Capital Boom

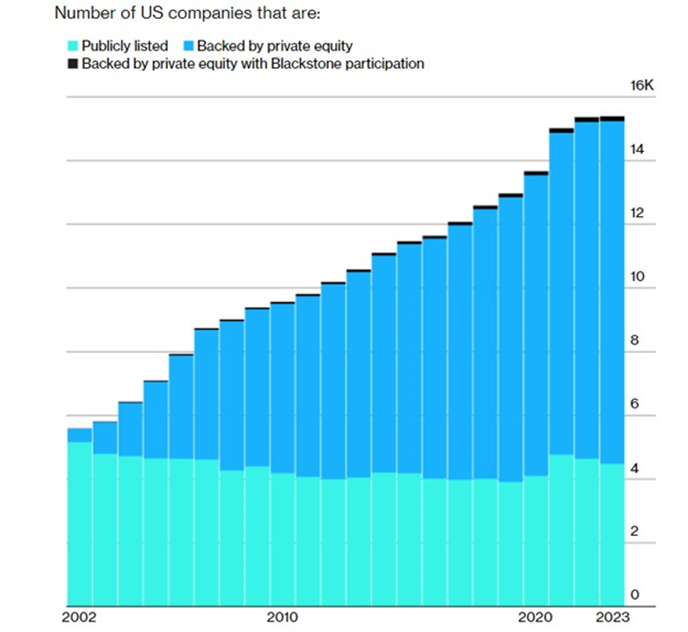

In recent years, a flood of private capital has surged into venture-backed companies and late-stage startups. Firms like Blackstone, KKR, and Sequoia have raised record-breaking sums, offering growing companies ample funding without the hassle of going public. Why endure the quarterly scrutiny of Wall Street analysts when you can raise billions behind closed doors?

Source: Public company data from World Federation of Exchanges; Blackstone and private company data from Pitchbook.

Note: Listed companies may involve double counting if companies are dual-listed on the NYSE and Nasdaq. Data as of June 2023.

Easier Access to Private Financing

Technology and market innovation have made it easier for startups to raise funds from private investors. Platforms like AngelList and Carta, and even crypto-based fundraising methods, have allowed companies to delay or bypass public listings entirely. As a result, companies are staying private longer—growing from scrappy ventures into $10 billion “unicorns” before they ever consider ringing the opening bell.

Shadow Banking and Non-Traditional Credit

The rise of shadow banking—non-bank institutions providing credit—has filled gaps traditionally handled by public markets. Hedge funds, sovereign wealth funds, and pension funds have all become alternative sources of capital, reducing the need for companies to access equity through IPOs.

The Regulatory Burden of Going Public

The post-2008 regulatory regime, led by Sarbanes-Oxley and Dodd-Frank, significantly increased compliance costs for public companies—especially small and mid-cap firms. These laws were designed to protect investors and increase transparency, but they also made the public route less attractive. Audit requirements, internal control mandates, proxy disclosures, and ongoing compliance costs can easily run into millions annually, discouraging many smaller companies from entering or remaining in public markets.

The Broader Policy and Macro Picture

It’s not just investor behavior—it’s also macroeconomic and policy-driven. A low interest rate environment pushed institutional capital toward riskier private deals in search of yield. Simultaneously, lax antitrust enforcement and market consolidation have allowed large firms to grow larger—often by buying out their smaller, would-be rivals before they even consider going public.

In short, government policy has been a major contributor to this change. The combination of easy private capital, heavy-handed public regulation, and light corporate consolidation oversight has fundamentally altered how companies fund their growth.

Consequences for Investors

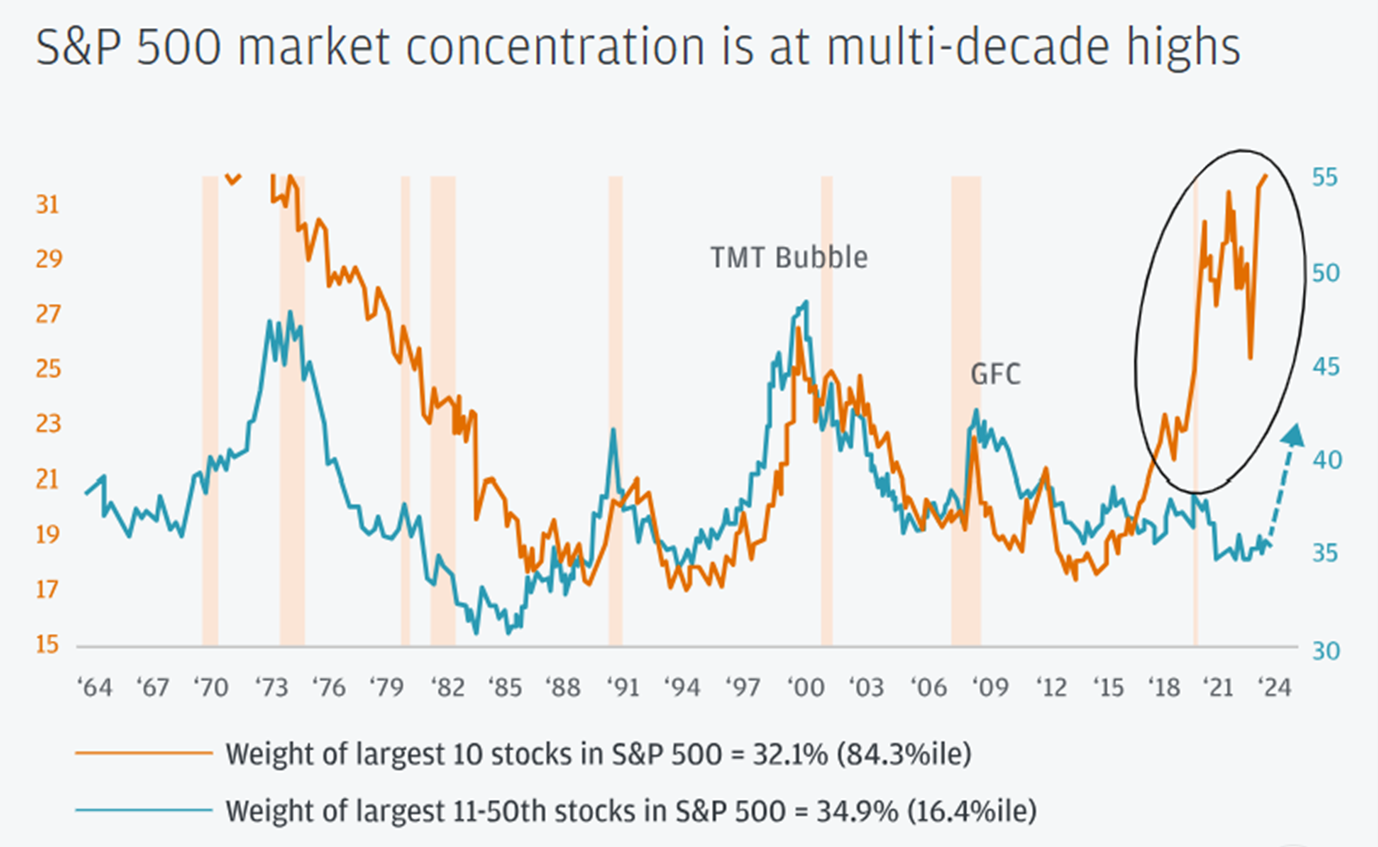

Source: J.P. Morgan Equity Strategy

Less Access to Early-Stage Growth

Historically, retail investors could buy into Microsoft, Apple, or Amazon while those companies were still in early stages of explosive growth. Today, those opportunities increasingly exist behind the closed doors of private markets, accessible only to venture capitalists or accredited investors.

Index Concentration Risk

The shrinking stock universe has led to increasingly lopsided indices. Today, the top 10 companies in the S&P 500 represent over 35% of its market capitalization, up from around 20% two decades ago. That means passive index investors may believe they are diversified, but in reality, they are heavily concentrated in just a few tech giants. This concentration exposes portfolios to idiosyncratic risks from a handful of companies, rather than the broad market.

Shifting Market Composition by Size

Even though there are fewer public companies overall, Morningstar’s market cap segmentation provides an illuminating perspective. Morningstar defines:

- Large-cap as the top 70% of total market capitalization,

- Mid-cap as the next 20%, and

- Small-cap as the bottom 10%.

Where Do We Go From Here?

The shrinking of the public market raises serious questions about access, fairness, and the long-term health of capitalism. Are we moving toward a world where wealth creation is increasingly privatized, restricted to insiders and early backers? Can policy changes encourage more IPOs, or will private markets continue to dominate?

Some regulatory fixes—such as reducing the burden of Sarbanes-Oxley compliance for smaller firms, or offering tax incentives for going public—have been proposed but rarely implemented at scale. Meanwhile, retail investors may increasingly rely on vehicles like interval funds or public-private hybrid funds to gain access to the innovation frontier.

Investors today must be more thoughtful than ever about diversification, risk, and opportunity. In a world of shrinking public choices, the smartest portfolios may need to look beyond the usual tickers and into new—and sometimes less familiar—territory.

Principle Wealth