Key Takeaways:

- Tax awareness may improve your after-tax investment returns

- Asset location and tax-loss harvesting can create investment portfolio efficiencies

- Converting pre-tax retirement funds into a Roth IRA may offer compelling tax advantages

The Long-Run Impact of Tax Efficiency

Some investors attempt to maximize returns by carefully researching different investment options to identify the best prospects, but overlook the impact of taxes on their portfolios. Morningstar estimates that over the past 93 years, the average investor lost up to 2% per year to federal income taxes.* As you can see in the table below, by comparing the after-tax returns for a hypothetical tax-efficient investor with a hypothetical non-tax-efficient investor, a 2% shortfall can really add up over time.

Source: Investment Returns Calculator, mortgageloans.com

Over a 25-year investment period, the tax-efficient investor accumulated significantly more than the non-tax-efficient investor, an amount that can make a real difference to your retirement and your legacy. It shows that after-tax returns are what really matter for investment growth over time.

We share three strategies that can help you invest more tax efficiently and maximize after-tax returns.

Strategy 1: Asset Location

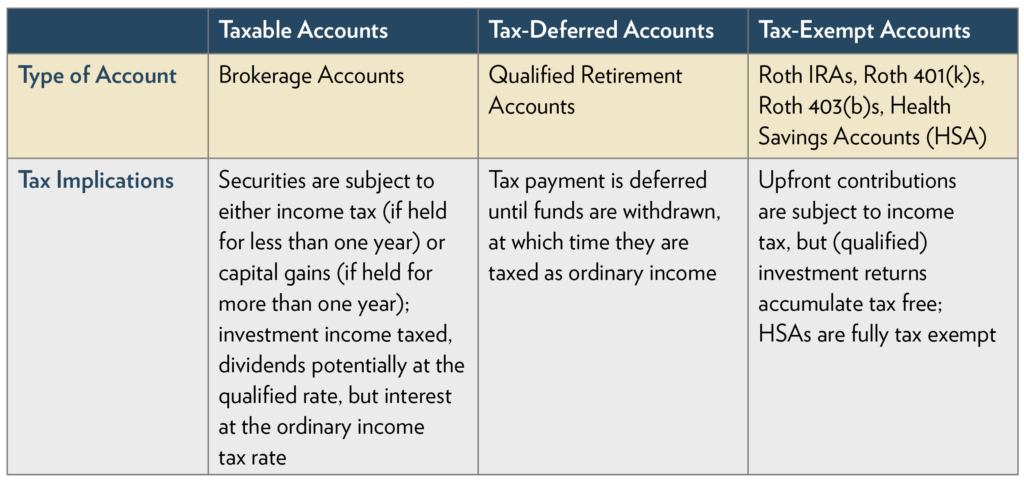

Although taxes should not be the primary driver of your investment strategy, implementing a thoughtful tax plan tailored to your specific situation can help you reduce your tax burden each year. A tax-efficient portfolio distributes your investment assets among taxable, tax-deferred and tax-exempt accounts in the most tax-efficient way for your situation. This ultimately lowers the tax effects on your investment portfolio and improves your after-tax returns.

Each investor’s asset location strategy should be personalized to his or her needs; however, it generally makes sense to put:

- The most tax-advantaged investments (such as individual stocks, equity index mutual funds, tax-managed equity funds, and tax-free municipal bonds or bond funds) into taxable accounts and

- The least tax-advantaged investments (such as bonds and bond funds and actively managed stock funds) into tax-deferred or tax-exempt accounts.

Strategy 2: Tax-Loss Harvesting

Sometimes, even an investment that has lost value can do some good. Tax-loss harvesting allows you to sell an investment that has gone down in value and replace it with a reasonably similar investment, using the loss to offset realized investment gains. Or, you can use the investment losses to offset up to $3,000 in income on a joint tax return in one year. And, unused losses can be carried forward indefinitely.

When selecting investments to sell for tax-loss purposes, consider choosing those that no longer fit your strategy, have poor prospects for future growth, or can be easily replaced by other investments. Generally, focusing on short-term losses provides the greatest benefit because they are first used to offset short-term gains, which are taxed at a higher marginal rate. In addition, consider your cost basis, the price you paid for a security plus any brokerage costs or commissions. If you have acquired multiple lots of the same security over time at different prices, designating the shares with the highest cost basis to sell increases the amount of realized loss.

Strategy 3: Convert Pre-Tax Retirement Savings into a Roth IRA

You can also potentially reduce your tax liability by converting your retirement savings into a Roth IRA, which offers two compelling benefits. First, qualified withdrawals are tax-free (because you pay income tax at the time of conversion) and second, the assets are not subject to Required Minimum Distributions (RMDs). A conversion may make sense under certain circumstances. You need to consider whether:

- You will move to a higher (or lower) income tax state in retirement. Even if you anticipate your federal tax rate will not change, the state income tax you are subject to is a factor in determining whether converting the assets will lower your taxes. A conversion may make sense if the tax you would have to pay at the time of the conversion is lower than what you would expect to pay in the future when you need to draw on your retirement assets.

- You will need the income from distributions to help fund your retirement. Traditional IRAs, 401(k)s and some other employer-sponsored retirement plans require you to start taking distributions beginning in the year you turn 72, and penalties are applied if you miss taking them. If you don’t anticipate needing the funds, you may not want to have to take the distributions, which would add to your taxable income. And reinvesting the unwanted distributions into a taxable investment account may also reduce your after-tax return. With a Roth IRA, you do not have to take the RMD.

- Distributions will impact your Medicare costs. The amount you convert into a Roth IRA is treated as income in the year the conversion takes place, which could raise your modified adjusted gross income to above the Medicare surtax threshold, $200,000 for single taxpayers and $250,000 for joint taxpayers for 2020. The additional Medicare tax rate is 3.8%.

- Your heirs will be subject to a higher (or lower) tax than you. Inherited IRAs, with their RMDs, could add to your heirs’ taxable income when they are in their peak earning years. However, a Roth conversion may not make sense if your heirs are likely to be in a lower tax bracket than you. In addition, if you plan to leave the assets to a charitable organization, know that traditional IRAs can typically be left to a non-profit without a tax bill for either party.

Your Sounding Board

There are many factors to consider when creating a tax-efficient investment strategy. As always, we are here for you to help you create a customized plan to meet your needs, and we welcome you to contact us with any questions you may have.

All the best,

John Hannigan

*How to invest tax efficiently, fidelity.com